Financial Crisis: GR Neighborhoods and the HOLC Map

by Matthew Daley, Grand Valley State University

published: July 7th, 2010

During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Grand Rapids was among the nation’s leaders in the percentage of owner-occupied homes. The city’s furniture companies and bankers collaborated to encourage this high rate of homeownership among factory workers as a way to ensure a stable workforce and to help prevent strikes and union organizing. Since much of the furniture output was destined for private homes, the health of the city’s economy depended on continued expansion of homeownership and the purchase of items to fill them. Though the 1929 Stock Market Crash is marked as the start of the Great Depression, the collapse of Michigan’s banks in February 1933 had a far more devastating impact. The collapse of the banks would be part of redefining homeownership, not only in Grand Rapids, but also the United States. (Find more information to your right in Related Items)

In January of 1933, Michigan's two largest financial organizations, the Detroit Bankers Company and the Guardian Detroit Union Group, could no longer conduct business and requested emergency loans from the federal government's Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC). In an effort to halt the spread of the financial crisis, newly elected Governor William Comstock took an unprecedented step; he closed the state's banks for one week, starting February 14, 1933. Many other states quickly followed suit.

The Grand Rapids Savings Bank, which served as the primary financial entity to city government, was not tied to the Union Group, but its instability occurring at the same time meant that the city's payroll and investments were threatened. In desperation, the city's leaders attempted to extricate or salvage funds, going so far as to invest $500,000 to help the bank reopen, all to no avail. When the bank closed the city found itself with few funds and the holder of nearly four-dozen mortgages; it was forced to request funds from the RFC to make payroll and its relief rolls. Homeowners were left in uncertainty, making payments, if they could, to banks that had swallowed their savings and offered no clear line of title to their homes.

The Roosevelt administration moved quickly to remedy the crisis. By March 1933 viable banks had reopened, and the federal government used them to start stabilizing the housing market; in Grand Rapids these included Old Kent Bank and the Grand Rapids Industrial Bank. Acts of Congress created new agencies that included the Emergency Banking Act to restructure banks, and the Home Owner's Refinancing Act on June 13, 1933. The latter created the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), an agency charged with helping to restructure mortgages and providing more liquid capital to banks to address the immediate crisis.

Before 1933 home mortgages were short-term balloon instruments that ran three to five years and did not amortize, which meant a large final payment or a new mortgage at current interest rates. When troubled banks recalled loans, they would not or could not offer refinancing and homeowners who were unable to make the large final payment lost their property. However, even after banks took possession of the homes, the diminished property values meant a loss for the bank. The HOLC and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) used federal government backing to offer new loan instruments.

While the HOLC and the FHA did not solve the problems of the Great Depression, they are among the most tangible reminders of that time. A change in how housing was valued was required in two major ways. First was the appraisal process for tax purposes by municipalities. Instead of different criteria being used by cities and private lenders, the forms began to align based on a standard set of guidelines. Since housing values had fluctuated wildly after the banking collapse, the FHA required that municipalities reassess all properties by the new system. Grand Rapids carried out the appraisals during 1936-1937 using forms, photographs, and diagrams. The system remains essentially the same to the present day.

The second impact of the HOLC and the FHA came through the long-term assessment of a property's value. Instead of short-term mortgages that required reassessment every few years, HOLC and FHA mortgages now ran into decades and required a judgment over a broad variety of factors in the life of neighborhoods, not just the individual finances of a potential homeowner.

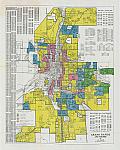

One of the most powerful visual documents of this change in outlook comes from the HOLC's maps made between 1935 and 1937. These color coded maps and their survey sheets offer an insight into how a combination of local, state, and federal appraisers, realtors, politicians, and community leaders viewed the long-term prospects of neighborhoods. Local leaders would play an important role in creating these views and help to shape the future of cities during the coming decades

Maps made by the HOLC and other entities at the local, state, and national level would help improve housing standards, but also target sites for freeway construction and public housing. The new mortgage system favored new housing in suburbs instead of cities and reoriented families out of Grand Rapids and into the new areas around it. Today's mortgage crisis and its outcome could have a similarly large impact on how we think about home in the twenty-first century.

An interactive version of the HOLC Map

Bibliography

Items available at the History & Special Collections Dept., Grand Rapids Public Library

- Badger, Anthony J. The new deal: the depression years. 1933-40. New York: Macmillan, 1989.

- Tottis, James W. The Guardian Building: Cathedral of Finance. Wayne State Univ. Press, 2008.

- Watkins, T.H. The Great Depression: America in the 1930s. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1993.

facebook

facebook