The Outhouse Comes In-house

by Diana Barrett

Henry Barnard, in an 1854 edition of School Architecture, cites the example of a three-story Boston primary school with privies for boys and girls moved indoors and located on each of the three floors. Highly unusual for the time, it does demonstrate that early technology was available, probably more apt to be found in a private school than public. Many schoolhouses of that time had no privies on the schoolhouse site, much less indoors. When privies were moved indoors in Grand Rapids schools, they were housed in school basements.

The various types of sanitary facilities most often used by schools during the 19th century were:

|

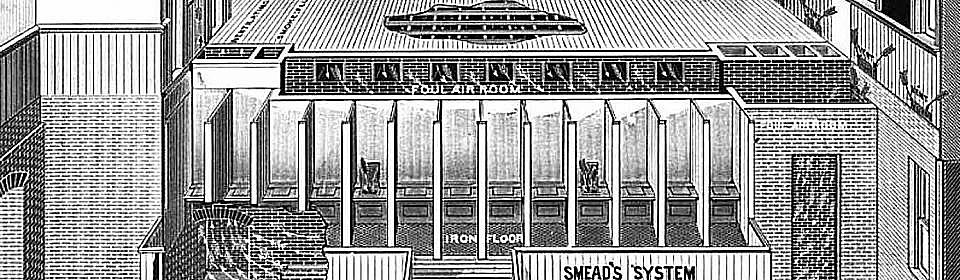

Privy vaults – A term used by municipalities, which never used the term ‘outhouse’ although that is what they were. School-sinks or sinks A row of connected privy vaults with separate doors. Each compartment would have been about 2½ ft. by 3¾ ft. with individual wooden seats, usually 18 inches high. Later the vaults were lined with concrete and connected to sewers. Supposedly a school janitor would flush them once a day with water piped into the trough. They acquired the name because they were first used for schools, but were also commonly found behind apartment houses or tenements. Water closets Similar to school-sinks, but moved inside, almost always placed in the basements of schools. Smead dry closet A method using heat to evaporate moisture from fecal matter so it became a powder that could then be dispersed through the outside ventilating system. Isaac D. Smead, who was more successful with his Ruttan Heating system, devised the system. |

Plumbing Inspectors Arrive on the Scene

Around 1890 plumbing inspectors began to make an appearance in larger cities of the country. The main source of employment for a plumber at the turn of the century, quite different from today, would have been connecting gas lines, steam lines for radiators, and sewer hook-ups. Grand Rapids deemed adding a plumbing inspector to the public payroll a positive move in 1900, although not everyone was in agreement. Henry N. Thompson, a practicing plumber, accepted the position on November 3, 1900,[1] and within two weeks the Board of Health, working with Thompson, had written the first draft of an ordinance that would govern the plumbing of every building in the city. It introduced some radical technical changes, such as the kind of pipe to be used and a standard thickness of all pipes and drains, but the most eye-opening regulation introduced read, “and sewers opening into sleeping rooms would be strictly forbidden.”

As expected, not everyone—including many landlords and plumbers—was in favor of such drastic changes, and it took quite some time to put the new practices in place. The Board of Health was of the opinion that the work of Inspector Thompson would be a great benefit to the health of the city, especially in the prevention of diseases carried by sewer gas.[2]

The public schools immediately became a prime target of Inspector Thompson. Henry School was one of the first to gain his attention due to complaints of the alleged unsanitary conditions of the building. The Smead system—yes, the same Isaac D. Smead—disposed of the refuse from the dry closet by cremation at certain intervals, but because of the stench permeating the building it could not be burned as often as necessary. A popular installation for schools and large buildings in other cities, it appears that Henry School, the Union Primary School, and the Diamond St. School, which was acquired during the 1891 annexation, were the only Grand Rapids schools using Smead’s dry closet.[3]

A potential danger to the health of children and teachers existed with Smead’s dry system, which reduced the fecal matter to powder by heat. If the draught of the ventilating shaft was defective, or was not maintained by the janitor, a reverse current of air could spread the powdered matter throughout the building through the ventilating system.[4]

According to the Board of Education Report for 1879-1880, Central High School, Union School, and the existing primary schools do not have water closets, or some variation of indoor facilities.

The 1891-92 Board of Education Annual Report details the following schools with indoor facilities:

|

Union Primary |

Smead dry closets |

|

S. Division St. |

water closets |

|

Fountain St. |

water closets |

|

W. Leonard |

water closets |

|

N. Ionia ST. |

water closets |

|

Center Ave. |

water closets |

|

Henry St. |

Smead dry closets |

|

Straight St. |

water closets |

|

S. Ionia St. |

closets in basement (not specified) |

|

Seventh St. |

closets in basement (not specified) |

|

Madison Ave. |

closets in basement (not specified) |

|

Congress ST. |

water closets |

|

Diamond St. |

Smead dry closets |

|

Central |

closets in the basement (not specified) |

|

Union School |

no mention of closets |

Inspector Thompson’s investigation at North Division Street School in 1902 revealed that public school children were living in an unsanitary and unsafe atmosphere. Privy sinks were found clogged up, incased in wood rendered soggy and rotten with wastewater and giving off evil smelling odors. Plumbing arrangements in Fountain Street School were condemned. The inspector remarked, “Even the most modern schools have been built in a slack manner without proper ventilating flues. The Central High School plumbing is as bad as any,” [5] although it had been built in 1892.

When the water level was high in the West Side ditch, a drainage canal, sewage would back up into basements and low-lying areas. By 1903 sewage had leaked through the sewer tile beneath the basement of Sibley School to such an extent that when the basement floor was taken up a regular cesspool was revealed.[6]

Board of Health Condemns City Schools

The Board of Health condemned the general plumbing in thirty of the city’s school buildings, including both high schools, due to the report of the plumbing inspector in 1904. Because the horrendous conditions in the city’s schools are so graphically described, the entire newspaper article, quoting Inspector Thompson’s report, is included.

“Deplorable unsanitary conditions in several of the public schools were revealed in the report of Plumbing Inspector Thompson made to the board of health this afternoon. The report was a long one, six typewritten pages being devoted to Madison Avenue School, the Central High School, the Central Grammar School, and Turner Street School. He says that in a general way the unsanitary conditions are much the same in all the school buildings.

At Madison Avenue School the plumbing inspector found that the drain is of tile, which is defective under the basement floor, allowing the escape of sewage, saturating the earth so that some of the sewage has found its way through the joints of the brick floor and spread in a pool several inches in depth along the base of the partition wall adjoining the boys’ toilet room.

One of the most unsanitary conditions exists in the cooking room where the intercepting trap is located beneath the basement floor. The surface extension from this trap is brought up to a point just below the wooden floor, there being no soil pipe extension to above the roof for ventilation. The poisonous gases, generally termed sewer gas, are emitted from organic matter which coats the inner surface of the drains and sewers, and which accumulates in unventilated branches of the drainage system known as dead ends. These gases are constantly escaping through the open pipe into the building. In the boys’ toilet room is located a latrine or privy sink, which consists of a cast-iron trough about thirty feet long, twelve inches deep, and fourteen inches wide, half filled with water. The trough is incased in wood that emits a bad odor. The filth remains in the latrine for hours at a time. In the girls’ toilet room the latrine were found in practically the same condition. Various pipes leading to the sewer in other parts of the building were found to be without traps and not vented, allowing free escape of sewer gas into the building.

Mr. Thompson makes the following recommendations in order to place the plumbing and drainage of all the school buildings in a sanitary condition and in accordance with the rules and regulations of the board of health.

‘I would recommend that the tile drains be removed and cast iron drains installed; that the latrines or privy sinks be removed and automatic flushing tank closets be installed. All woodwork should be removed from all plumbing fixtures. All main soil pipe traps and surface vents should be located in the yards at a safe distance from the buildings. All lavatories and sinks should be property trapped and vented. All brick floors in toilet room should be removed and floors should be constructed of hard and smoothly finished cement. All rainwater conductor pipes, where passing through the ground, should be of cast iron to a safe distance from the building, so that there would be no danger of foundation walls becoming wet and unsanitary, caused by leaking joints. The water supply pipes to all urinals should be rearranged so that t he water would be confined to the slabs it is intended to flush instead of keeping several yards of the floor wet where it is not necessary.’ ”[7]

Into the Twentieth Century

By 1907 the city had a new plumbing inspector, Henry G. Griffin. He picked right up where Thompson left off by declaring the urinals and closets at South Division School unsanitary and that new ones of modern design should be installed. The radiators that heated the rooms on the first floor were hung from the ceiling in the toilet rooms, forcing the foul air from the toilet rooms into the school rooms above.[8]

Mr. Griffin had discovered that his job was more strenuous than he expected. He declared that when was done pedaling around for a day he can do no more than fall off his bicycle. He requested an assistant.

The Board of Education Annual Report of 1909 states, “Finally all buildings will have toilets with sewer connections except Walker (sewer not accessible).” But in 1913, almost ten years after the damning report by Plumbing Inspector Thompson, the old schools such at Sheldon, South Ionia, Second (Grandville), and Lexington were still plagued by sanitation and ventilation problems. At Sheldon School there was also, “a fire risk with the iron stack from the heating plant ascending through the lower floor corridor directly adjacent to the only two stairways giving access from the second floor. The sanitation, because of the old style plumbing, was bad and the entire cluttered basement was filled with foul odors.”[9]

Sheldon School played a role in the political destiny of George W. Welsh who eventually became city manager and mayor of Grand Rapids after serving as state representative, speaker of the House, and Lt. Governor. His political career began in 1913 when he was recruited to run against the incumbent alderman of the 11th ward. His talents had been noticed when Welsh was part of a successful protest brought before the Board of Education by neighborhood parents who demanded replacement of the Sheldon building. Welsh’s daughter attended the condemned school.

Have no fear that Grand Rapids was standing alone as an embarrassing example with a disgusting record of sanitation in its schools. Newspaper across the country mimic those of Grand Rapids in reporting school buildings condemned by the Health Inspector and the Plumbing Inspector; as indicated by two reports from opposite sides of the country. In Trenton, New Jersey the story beneath the headline Pupils’ Health in Peril reported, “When the special committee visited the schools using the Smead system they found that the rooms were filled with foul air and instead of there being a vent a lighted candle placed at the register would be blown inward.”[10]

On the opposite coast in Portland, Oregon, Menace to Health headlines an article where we read that the Health Officer and Plumbing Inspector found, “. . . at schools disagreeable and unwholesome odors emanated from the closets and sewage pipes . . . others having vaults, some of which are flushed out but once a day, such bad odors were perceived that the immediate use of disinfectant was recommended.”[11

[1] GR Herald, 11/3/1900, p3

[2] GR Herald, 11/19/1900, p3

[3] Bd. of Ed. Annual Report, 1891-92, 12-18

[4] Wheelwright, Edmund March. School Architecture. Boston: Rogers & Manson. 1901, p 275

[5] GR Press, Dec. 4, 1902, p 8

[6] GR Press, Dec. 9, 1903, p 2

[7] GR Press, Nov. 10, 1904, p9

[8] GR Press, Jun 7, 1907, p7

[9] GR Press, April 10, 1913, p14

[10] Trenton Evening Times, 10/7/1894

[11] Morning Oregonian, 9/30/1898

facebook

facebook